If you have not yet read Mamari Stephens’s article in E-Tangata on welfare laws that beg to be broken, read it here. It’s excellent.

One thought struck me: there are parallels between crappy welfare law (and practice) and crappy abortion law (and practice). Both systems carry the implicit expectation that women should act against their own interests.

Stephens discusses how welfare law carries the presumption a women with a man in her life will receive financial support from him, which is the rationale for reducing the benefit a woman in such a relationship receives. The welfare system reinforces the prescriptive nature of that expectation – by reducing her benefit the law forcibly shifts her dependence onto a man who may turn out to be unreliable. Or worse.

Women maintain the independence their benefit gives them and their families by lying to WINZ about their circumstances.

Abortion law carries the presumption women should not make their own decisions about the contents of their uteri. Rather, they must apply to the medical profession (explicitly presumed to be male) for the approval of two certifying consultants in order to end a pregnancy. The grounds for abortion in the Crimes Act and the bureaucracy created by the Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion Act leave the reader with the correct impression the Royal Commission intended that women should carry most pregnancies to term, like it or not.

Women with unwanted pregnancies maintain their bodily integrity by lying to the certifying consultants that their mental health would suffer if they were forced to carry the pregnancy. Certifying consultants assist them by pretending to believe them.

In both cases, women are forced to lie in order to keep something that would cost them and their families dearly if they had to give it up.

And then there is the stigma associated both with being on a benefit and getting an abortion. In a classic double bind, a woman with an unwanted pregnancy is forced to choose one to avoid the other. She gets judged no matter which she chooses.

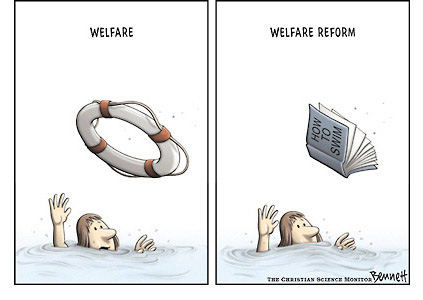

Stephens writes “we need policies that will incentivise law keeping rather than law breaking. Let’s discuss those possibilities.”

For a country that supposedly reveres the rule of law, it’s long past time to start those discussions.