by Dame Margaret Sparrow

Setting the scene

Looking back to 1961 it was a year of major international tension but also significant achievements. In January John F. Kennedy was sworn in as President of the United States. The cold war was omnipresent and worsened with the USSR testing large nuclear bombs then masterminding the building of the Berlin Wall. American citizens were encouraged to build fallout shelters. The space race between USSR and the United States escalated. In April, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin completed the first orbit of Earth, and less than a month later Alan Shepard became the first US man in space.

In the United Kingdom, marches were held by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The World Wildlife Fund and Amnesty International were both launched. The UK began talks to join the EEC. The Beatles started performing at the Cavern Club, in Liverpool.

In New Zealand, Keith Holyoake was the Prime Minister and Viscount Cobham was the Governor General. We celebrated the first national Waitangi Day. One of the last outbreaks of poliomyelitis caused seven deaths. The death penalty was finally abolished. A change to liquor licensing meant for the first time restaurant diners could legally be served wine with their meal. The population of New Zealand was 2.5 million. Over 65,000 kiwi babies were born, the most fertile year of the post-war baby boom. Illegal abortionists plied their trade and from time to time were prosecuted; seven were convicted. Six women died from an abortion.

The Pharmaceutical Industry

Something sinister was percolating which would have a bearing on the control of all drugs. Thalidomide was first marketed in 1957 in West Germany, where it was available over the counter for anxiety and insomnia. It later became popular for morning sickness in pregnancy. However in 1961 it was associated with congenital defects in babies. Due to public outrage the medication was withdrawn from the market in Europe in November 1961. It is estimated that the total number of embryos affected by use during pregnancy was at least 10,000, of which about 40% died around the time of birth. Those who survived had limb, eye, urinary tract, and heart defects. Its initial entry into the US market was prevented by Dr Frances Kelsey of the FDA who was concerned about the lack of safety evidence. For resisting the pressure from promoters and averting a thalidomide disaster in the US she received an award from President Kennedy.

Thenceforth much needed changes were made throughout the world, including in New Zealand, to procedures for the approval of drugs. This came at a time when the burgeoning cost of pharmaceuticals also mandated a scrutiny of the system.

Right: Dr Frances Kelsey (1914-2015) who refused to approve thalidomide in the USA.

Prior to 1961 the introduction of new drugs into New Zealand, under the Food and Drug Act 1947, could best be described as laissez faire. As long as drugs complied with the British Pharmacopoeia or some other recognised standard there was no need for local clinical trials, or testing to determine quality or safety. There was no formal inspection or regulation of manufacturers, importers, wholesalers, or distributors. The system relied on trust; that importers would access new medicines from reliable sources and the medical profession would ethically prescribe and chemists ethically dispense. Free medicines had been introduced with the 1938 Social Security Act and if a medication was deemed necessary it was funded and listed on the Drug Tariff. Although hormonal treatments for medical conditions by a specialist might be funded, the same pills used for contraception were not.

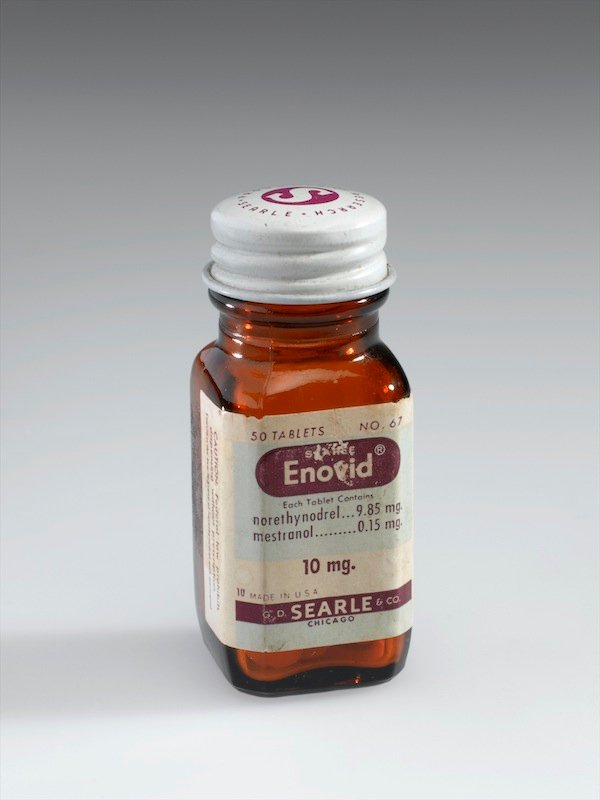

When Enovid, manufactured by Searle (US), was approved for use for medical conditions (menstrual disorders and endometriosis) by the FDA in June 1957, its distribution was expanded through Searle (UK) under the name Enavid. New Zealand obstetric and gynaecology specialists kept abreast of trends and were able to order supplies of this through N.M. Peryer, a Christchurch-based licensed wholesaler.

When Enovid was approved for use for contraception in May 1960 the potential for prescription by general practitioners widened the market but because of side effects, the lower-dosed Conovid became the preferred drug. In December 1961, the United Kingdom Minister of Health Enoch Powell announced (enviously) that the contraceptive pill Conovid would become available via the NHS at a subsidised price of two shillings per month.

In 1962 Conovid-E was introduced in New Zealand as a contraceptive. All three drugs were imported into New Zealand.

Enavid (UK) 10mg norethynodrel + 150mcg mestranol (from 1957 mainly for specialists)

Conovid 5mg norethynodrel + 75mcg mestranol (from 1961)

Conovid-E 2.5mg norethynodrel + 100mcg mestranol (from 1962)

The original packaging of Enovid (US) was in bottles of 20, 50, and 250

It was the pharmaceutical representatives who liaised with chemists and doctors, educating, advising on the availability and providing free samples. There were no regulations regarding the training or qualifications of these detailers.

Barbara Brookes recounts that in February 1961 the Medical Officer of Health in Hamilton wrote to the Director-General seeking clarification because the local president of the Pharmacists’ Guild told him that travellers were visiting chemists, providing Tabs Conovid and suggesting that they could be sold to the public. The Department ruled emphatically that they could only be sold by pharmacies on prescription.

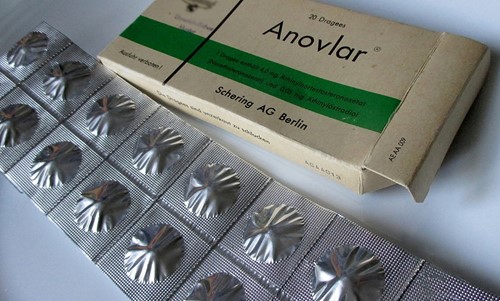

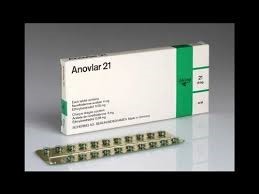

Meanwhile in 1960 the West German pharmaceutical firm, Schering AG (now Bayer HealthCare) were conducting trials in Australia of Anovlar = 4mg norethisterone acetate + 50mcg ethinyloestradiol. In February 1961 Australia was the first in the world to approve this contraceptive and it would have been distributed in New Zealand at about this time. At first Anovlar came in strips of 20 but in July 1964 the packaging was changed with 21 pills encased in foil and labelled with the days of the week to improve compliance.

Original packaging of Anovlar in 1961.

Anovlar new packaging in 1964.

Schering representatives visited general practitioners persuasively marketing their product and distributing free samples. On 3 July 1962 NZ Truth reported that after a year there was an increasing demand for the two most popular pills then available, despite the relatively high cost: Schering’s Anovlar, the little green pills, which cost 28 shillings per month and Conovid, little pink pills, manufactured by Searle (UK), which cost 31 shillings per month.

This was a lucrative market and competition from a number of other firms would soon lower the price. By 1970 there were 14 pharmaceutical firms offering 34 different brands of contraceptive pills. Schering had added Gynovlar, Eugynon and Neogynon. Searle had added four different strengths of Ovulen. In addition to these so-called combined pills, containing a progestogen and an oestrogen, the first progestogen-only pill Normenon appeared in that list.

The New Zealand Department of Health

Unlike its counterpart in the UK, the Department of Health in New Zealand wanted nothing to do with birth control. In April 1961 when the Minister of Health was invited by Sir Julian Huxley to be included in the World Tribute to Margaret Sanger he was advised to send a curt refusal. Internationally overpopulation was a concern but this was considered irrelevant in the New Zealand context. Even contraception was regarded as controversial let alone population control and eugenics which Margaret Sanger had supported.

A 1961 statement declared that the Department considered ‘birth control was solely a question of public morals, not of public health’. This policy was challenged on a number of occasions especially as it prevented Public Health Nurses from giving advice on family planning. In December 1966 the Department sent a circular memo to all Medical Officers of Health emphasising that family planning was primarily the role of the family doctor, or if there was none, a Family Planning clinic.

In 1962 an amendment to the Food and Drug Act required notification of any new and changed medicines through a notice in the New Zealand Gazette. Medicines that were on the market at the time were accepted without evaluation (grandfathered). The approval of Enavid, Conovid and Anovlar were duly gazetted, effective from 1 July 1962. In 1962 it became mandatory to obtain consent for clinical trials and in 1965 the Committee on Adverse Drug Reactions was formed. In 1969 control was transferred from the Division of Public Health to the Division of Clinical Services and further regulations were introduced.

The medical profession

Until the arrival of the Pill the main methods of contraception were withdrawal (unreliable), condoms (embarrassing to purchase and of poor quality), diaphragms and caps (few doctors were trained to fit these correctly), natural family planning (abstinence not popular), and once a family was complete, female sterilisation (vasectomy was not yet available in New Zealand).

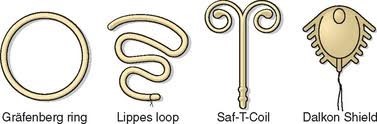

An older method, the IUD, had gone out of favour. In 1961 a New Zealand gynaecologist Dr A.M. Rutherford published a paper in the NZ Medical Journal on his less than satisfactory experience with the Gräfenberg ring. However, in 1962, an important IUD conference was held in New York drawing 60 people from 11 countries and this restored some faith in the method. A second conference in October 1964 attracted 600 people from 44 countries. The IUD was back. Coinciding as it did with the introduction of the Pill this was the start of what demographers call a contraceptive revolution.

1960s IUDs

But in 1961 there were few attractive contraceptive options and the Pill met an unfilled need for reliable fertility control. Writing a prescription was a familiar routine for doctors and that put them back into their comfort zone. Even those who previously disapproved of ‘messy’ birth control methods were converts. But it didn’t happen overnight.

An article in the Dominion 12 April 1961 on the Women’s page (more often featuring millinery styles) carried the headline HORMONE DRUG TABLETS NOT FAVOURED and continued: ‘The first synthetic hormone drug tablets which temporarily suppress ovulation (oral contraceptives) to appear on the New Zealand market, are being greeted with some suspicion by Wellington doctors. Specialists and general medical practitioners approached yesterday on the practicability and advisability of using the tablets were generally agreed that as yet, they would not prescribe them.’

However some GPs were already providing contraceptives through those free samples from enthusiastic, commercially incentivised, pharmaceutical reps. The uptake of the Pill by New Zealand women was described as phenomenal and one of the highest in the world. Writing in FPA’s Choice magazine in 1965 Professor Bonham estimated that 40% of all women at risk of pregnancy were taking the Pill. Some 100,000 packs were being sold each month.

Specialists were kept up to date through medical journals. The first advertisement in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (ANZJOG) by Schering, ‘Anovlar for Ovulation Control’, appeared in Vol. 1, No 2, June 1961.

Family Planning Association (FPA)

Leading up to 1961 the relationship between the medical profession and FPA was strained. The New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association (BMA) regarded FPA as a lay organisation encroaching on its territory. Matters came to a head when in February 1960 the ethical committee of the BMA advised its members that it was ‘unethical to refer patients to clinics’. Fortuitously in June 1960 Dr Alice Bush, a respected Auckland paediatrician, was elected president of Family Planning and this paved the way for constructive dialogue. Early in 1961 a deputation met with a special sub-committee of the BMA, and as a result the offending policy was reversed.

Although individual FPA doctors prescribed the Pill when it was considered appropriate the Association was very cautious in recommending the Pill and in the early years continued to promote barrier methods as first choice. This caution was mainly for reasons of safety and the unknown effects of long-term use. In an article in the Otago Daily Times on 12 July 1962 Dr Swyer, an eminent O&G consultant visiting from London roundly criticised the Association for ‘simply falling behind the times’ in regard to contraceptive practices. The article did not mention that the good doctor’s visit was sponsored by Schering.

In 1963 in the very first issue of Choice, a magazine for FPA staff and supporters, there was a balanced article on the Pill by Dr Ruth Black, a member of the Medical Advisory Committee, and the back cover of the magazine carried an advertisement for Anovlar. However it was not until the 1964 FPA conference that the Pill received an endorsement.

Other influences: The Press and Feminism

New Zealand magazine readers knew about the development of the Pill in the US from articles in Time, and Reader’s Digest but less was known about developments in Europe and the UK. New Zealand newspapers and women’s magazines tended to avoid the topic in the early years. Even the FDA approval in May 1960 was not a major news item. In New Zealand Enavid was not promoted as a contraceptive (although it could have been) and was not newsworthy.

The introduction of specific contraceptive pills (Conovid and Anovlar) in 1961 came in under the radar. There was no specific event such as an official announcement of scientific approval; no press conference, no launch, or symposium. Even the Australian approval of Anovlar in February 1961, the second country in the world to approve a contraceptive pill, went largely unreported. Pharmaceutical firms did not wish to create controversy or arouse opposition due to religious or moral objections. The revolution happened quietly in doctors’ consulting rooms throughout New Zealand.

The Pill is often portrayed as a symbol of women’s empowerment but that was not how it was experienced in 1961. That came later. The Australian Women’s Weekly did not feature an in depth article discussing oral contraception until 22 July 1964, when Rene Lecler contributed the ‘Latest Medical Survey of the Pill’. It became the highest selling issue of the decade revealing an unmet need for information which was useful for women. Women waited until 1971 for the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective to publish Our Bodies, Ourselves: A Book By and For Women.

The feminist view of the Pill was multifaceted and ranged from liberation to victimisation. It changed over time and is still changing. On the one hand, it was seen as advantageous to take what advances in medical science could offer. Women welcomed the much-desired control of their fertility and enjoyed the freedom to explore new goals in education and career. Many women wanted to be more independent and less reliant on a male partner. On the other hand others argued that women were being exposed to harm from experimental medication with possible long-term consequences. Many women suffered from serious adverse side effects. A few died. But women also died because of pregnancy or childbirth. Some worried that being sexually available might lead to exploitation by men and a change in relationships. Some wished to maintain cherished feminine roles. Caution was seen by some as a virtue, risk-taking as reckless. The personal became political with a focus on women’s rights and gender equality.

There were many questions. Why wasn’t there a pill for men? Were women at the mercy of profit-driven powerful pharmaceutical companies? Why wasn’t there more research on better methods of fertility control for men and women? What was the role of the government and health authorities? Should contraception be free? Did there need to be such gate-keeping by the medical profession? What about a woman’s choice? These questions are still being asked.

Resources used in the preparation of this article

- Barbara Brookes, Claire Gooder, Nancy de Castro. Feminine as her Handbag, Modern as her Hairstyle.NZ Journal of History, 47, 2; 2013.

- Ministry of Health. History of Medicines and Medical Device Regulation in New Zealand: Regulation before the current Medicines Act 1981.

Regulation before the current Medicines Act 1981 (medsafe.govt.nz)

- Helen Smyth. Rocking the Cradle: Contraception, Sex and Politics in New Zealand. Wellington: Steele Roberts, 2000.

- Ian Pool et al. New Zealand’s Contraceptive Revolutions Population Studies Centre, University of Waikato, 1999.

- H1 Archives New Zealand, Wellington (Health Department files).

Contraceptives 1940-1965.

Maternal and Child Welfare: Birth Control 1941-1966

Social Security: Pharmaceutical Benefits Searle and Co (NM Peryer) 1961-1964

March 2021